Plaque to commemorate 50th anniversary of Hurricane Hazel

Record-breaking storm hit the west end the hardest

By Tom G. Kernaghan

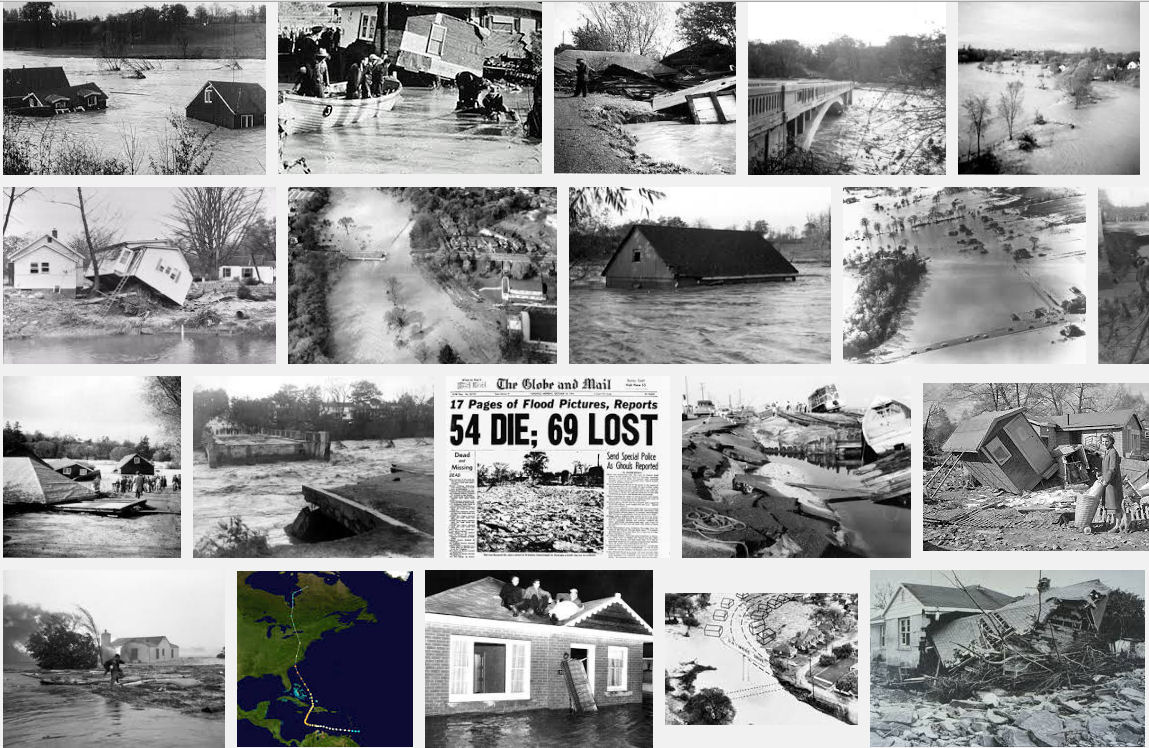

Fifty years ago on the morning of Oct. 16, Torontonians awoke to the inconceivable: their city ravaged by a hurricane. Hurricane Hazel had left 81 people dead, thousands homeless, and a city in shock.

And this year, on Oct. 14 at 1:00 p.m., the Ontario Heritage Foundation (OHF), the Humber Heritage Committee (HHC), and the City of Toronto will mark the hurricane’s 50th anniversary by unveiling a commemorative plaque at King’s Mill Park (under the Bloor Street viaduct by the Old Mill subway station).

“The purpose is to spark interest in learning what happened after” and during the storm, explains Wayne Kelly, the OHF’s plaque program coordinator. He adds King’s Mill Park is “emotionally significant” because during the hurricane most of the area was under water. Six metres up the bridge, marked in blue, is the high water mark, a poignant reminder of nature’s unpredictable power.

That unpredictability cost the city when after three days of rain, residents went to bed on the night of Oct. 15, 1954 convinced they were in for another safe but soggy night. Hazel had wreaked havoc in the Caribbean and Carolina, but here in Toronto, where hurricanes were a rarity, the storm was already old news. Misled by this cozy belief, which was supported by low-key weather reports, most expected Hazel to lose punch around the Allegheny Mountains before turning eastward.

They we were wrong. Worse, they were unprepared when Hazel pushed past New York and crossed Lake Ontario. As it reached the north shore it collided with a strong cold front. The result was catastrophic. With awesome force, its 72-mile-per-hour gusts and billions of gallons of rain turned the city’s full rivers into raging torrents, washing out 40 bridges, undercutting asphalt, tossing large vehicles, uprooting massive trees, submerging buildings, and carrying the flotsam of destroyed lives.

The storm changed the landscape, and inflicted $25 million in damage, particularly in the west end, with its vulnerable floodplains along the Humber watershed. As the rain pounded the city’s northwest region, it turned the Humber River into a monster.

“You could hear the roar of the river,” recalls Madeleine McDowell, chair of the HHC. “We didn’t know what it was. Take the sound you’d hear in a bad thunderstorm and multiply it by 50 or a 100.”

The destruction was staggering: the bridges at Bloor Street, Dundas Street, Old Mill, and Albion Road were badly damaged; and the Lawrence Avenue bridge at Weston Road and the bridge at Lakeshore Boulevard and the Humber River were washed out.

People were killed, with mind-boggling suddenness.

The residents of Raymore Drive paid a dear price for their proximity to the Humber River. The street was almost entirely obliterated when a damaged suspension bridge shot water and debris straight at it, killing 32 and leaving 60 families homeless. At nearby Etobicoke Creek, nine-month-old Nancy Thorpe clung to a neighbour as her entire family drowned. Down river, north of Old Mill, five Kingsway-Lambton volunteer firefighters lost their lives while trying to save two stranded teenagers.

The city mourned, and learned.

In 1957, four existing conservation authorities came together as the Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, now the Toronto and Region Conservation (TRC). Since then, motivated by core principles of public safety, education and action, the TRC has studied flood control, purchased floodplain lands, cultivated our vast parklands, and shared their knowledge with policymakers and the public, to help prevent future flooding.

(Gleaner News, Toronto)