It was a dark and stormy night

Hurricane Hazel hit with devastating swiftness

By Tom G. Kernaghan

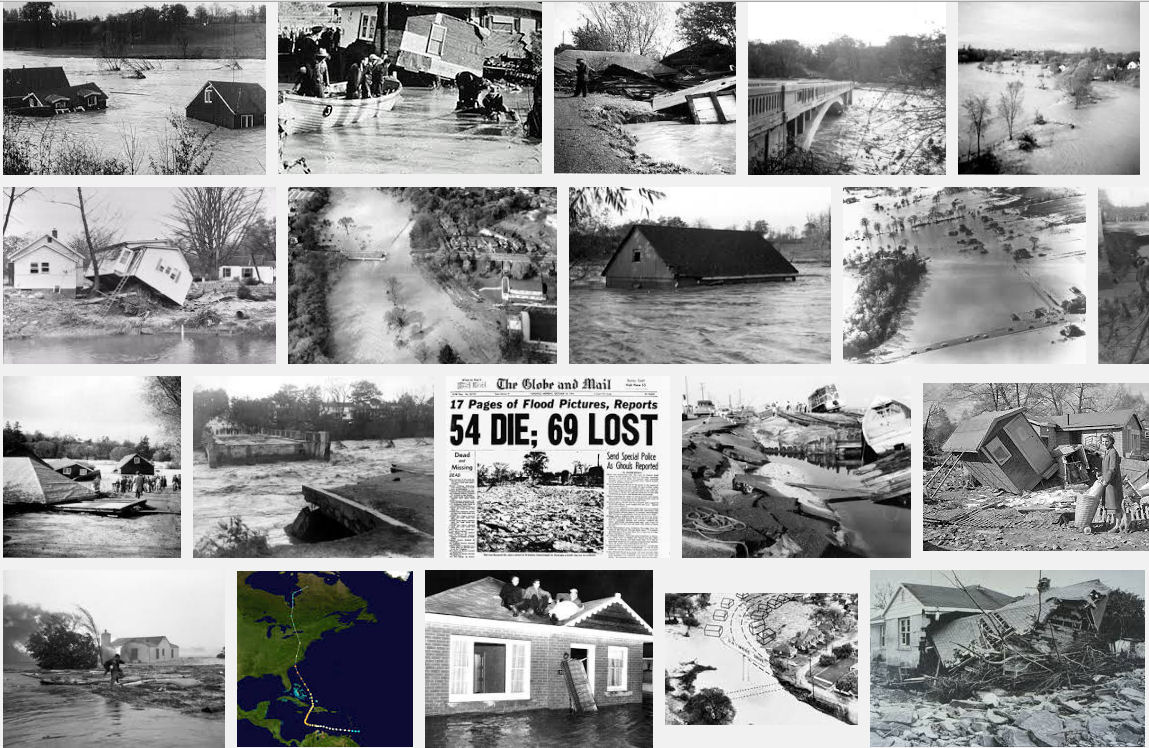

Fifty years ago on the morning of Oct. 16, Torontonians awoke to the inconceivable: their city ravaged by a hurricane. For the unfortunate people on lower ground or near riverbanks, Hurricane Hazel had made its terrifying introduction several hours before. Eighty-one people were dead, thousands were left homeless, and the city was in shock.

On the night of October 15, after three days of rain, many went to bed convinced they were in for another safe but soggy night. Hurricane Hazel had been wreaking havoc in the Caribbean and Carolina. But here in Toronto, Hazel was already old news. Here, hurricanes were nothing to fear. Misled by this cozy belief, which was supported by low-key weather reports, most expected Hazel to lose punch around the Allegheny Mountains before turning eastward.

They we were wrong. Worse, they were unprepared.

Hazel pushed past New York and crossed Lake Ontario. As the storm reached the north shore it collided with strong cold front. The result was catastrophic. Hazel unleashed its terrible fury on the saturated and unsuspecting city. With awesome force, its 72-mile-per-hour gusts and billions of gallons of rain turned full rivers into raging torrents, washing out bridges, undercutting asphalt, tossing large vehicles, submerging buildings, and ending lives with mind-boggling swiftness, particularly to the north and west of the city. The storm caused $25 million in damage.

Downtown, heavy rain and powerful wind pounded the lakeshore with ferocity, leaving Sunnyside Beach strewn with debris and refuse from the northeastern United States.

The rainwater rose well above curbs, hectoring pedestrians as they left work. Trains to and from Union Station were cancelled, traffic jams set records for delays, and heavy rain became a torrential downpour. The underpass on King Street West near Dufferin Street became hazardous, shallow rivers lapped against downtown buildings, and basements almost everywhere were flooded.

Eventually the rain eased.

Ken Steele, of Dovercourt Road, was walking home around 11:00 p.m. that night. He felt a strange, eerie calm in the air—it was perfectly quiet. It was almost like being in vacuum. He went to bed, unaware of the horror taking place on the Humber River.

Indeed, those living on relatively high ground awoke to the realization of Hazel’s full devastation. Roman Tarnovetsky, a seven-year-old living near Dundas Street West and Ossington Avenue, rode with his family to the lower ground of Queen Street and Roncesvalles Avenue to see the damage.

Hazel was a wake-up call to our need to better understand floods and how to control them. Many of those who lost their lives on that dark night had been living on cleared floodplains.

In 1957, four existing conservation authorities came together and formed the Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, now the Toronto and Region Conservation (TRC).

Since then, motivated by core principles of public safety, education and action, the TRC has studied flood control, purchased floodplains, cultivated our vast parklands, and shared their knowledge with policymakers and the public, in the hope of preventing future disasters.

“We have incredible parklands and valleys,” says Deputy Mayor and Councillor Joe Pantalone (Trinity-Spadina, Ward 20). “They are the defining elements of the city. We owe a vote of thanks to that interpretation [of the disaster].”

“This is an important anniversary,” he adds. “A lesson was learned. Disasters spur action. If people are smart, they will learn from them, and we did.”

(Gleaner News, Toronto)