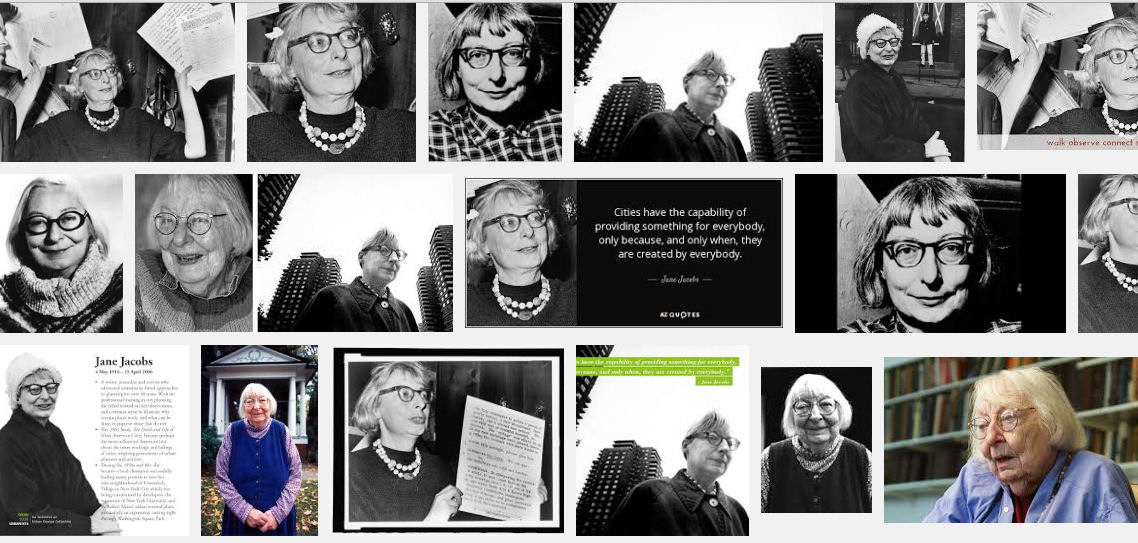

Original activist

Neighbourhood pays tribute to Jane Jacobs

By Tom G. Kernaghan

Like all prophets, her name preceded her. And though Annex resident Jane Jacobs passed away on April 25, the words and work of this legendary urban writer and activist live after her in the many books she penned, the initiatives she supported, and the people she inspired.

Jacobs wrote prolifically on planning, economics, and society’s ills, right up until the time of her death. But it was her seminal work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, that launched her career as a maverick critic of the urban planning establishment in particular, and experts and fools in general.

Rejecting abstract theories, Jacobs, born Jane Butzner in Scranton, Pa. in 1916, observed cities with astounding clarity, and strongly opposed the conventional view that cities were breeding grounds for evil and best avoided in favour of the suburbs. Rather, she advocated for their wonderfully intricate density, and argued their diversity make cities our greatest collective achievement.

“She was truly an original thinker and didn’t accept what the experts said,” said Nadine Nowlan, a local resident who, along with her husband, David, fought the Spadina Expressway proposal in the 1960s and early 1970s, arguably one of the most defining periods in the Annex’s history. It was in 1969 when they first met Jacobs, when she joined Stop Spadina, a large group of concerned local citizens who saw the expressway as a suburban encroachment on their way of life.

“I was very impressed,” said Nowlan. “She was a very friendly, open, and nice person. She was kind, warm, enthusiastic, and obviously very smart. I had great respect for her intellectual ability.”

By the late 1960s, Jacobs had already achieved intellectual leadership status among young activists and thinkers around the world for her fresh, brilliant ideas and her willingness to point fingers at those whom she regarded as the destroyers of cities.

But Jacobs was known for more than her acuity and journalistic pluck. When she moved to Toronto in 1968 with her architect husband Robert Jacobs and their three children, in order to help her kids avoid the draft, she had already gained notoriety for the role she played in stopping the Lower Manhattan Expressway in the late 1950s. Having triumphed in New York City, Jacobs arrived to the Annex armed with courage and wisdom born of her battle against fear, arrogance, and intransigence.

She had also faced criticism for her lack of formal education and training. But for Jacobs, who learned about cities by walking their streets as a struggling journalist during the Great Depression, this may have been one of her greatest strengths.

“She was worth listening to,” said Hamish Wilson, a Toronto environmentalist and bicycle activist. “She was independent and thoughtful. She had the ability to situate [her ideas] in a context of values and ethics.”

“She wasn’t shackled by preconceived notions,” said David Nowlan, who co-wrote The Bad Trip: The Untold Story of the Spadina Expressway with his wife, Nadine. “One of her distinguishing characteristics was her ability to come to her own conclusions about what she was seeing.”

Jacobs’ peerless combination of piercing intellect, practicality, and self-confidence was powerfully persuasive at the community level.

“We thought, ha, there’s a lady who knows what she’s about,” said Jean Houston, a local resident who attended an event to celebrate 35 years without the Spadina Expressway, held at Spadina House/Museum on June 2. Houston recalled Jacobs’ motivating presence at Annex Residents’ Association meetings over thirty years ago. “At the meetings she was very gracious…. But she could be very forceful!”

Though Jacobs could speak forcefully for what she believed in, she disliked force for its own sake. She sought discussions and collaboration, and encouraged others to seek an egalitarian approach to problem solving. Above all, she sought to improve the lives of those around her.

“From the minute you walked in the door [of her home], she was Jane and you were an equal,” recalled Adam Vaughan, a former Citytv journalist and candidate for city council in Trinity-Spadina, whose family was close with the Jacobs family while Vaughan was growing up. “She had this ability to change your mind on an issue, and make you feel smarter and better about yourself for doing it…. She taught me how to be a citizen.”

(Gleaner News, Toronto)