Remembering Hurricane Hazel

Local residents recall high winds and flooding

By Tom G. Kernaghan

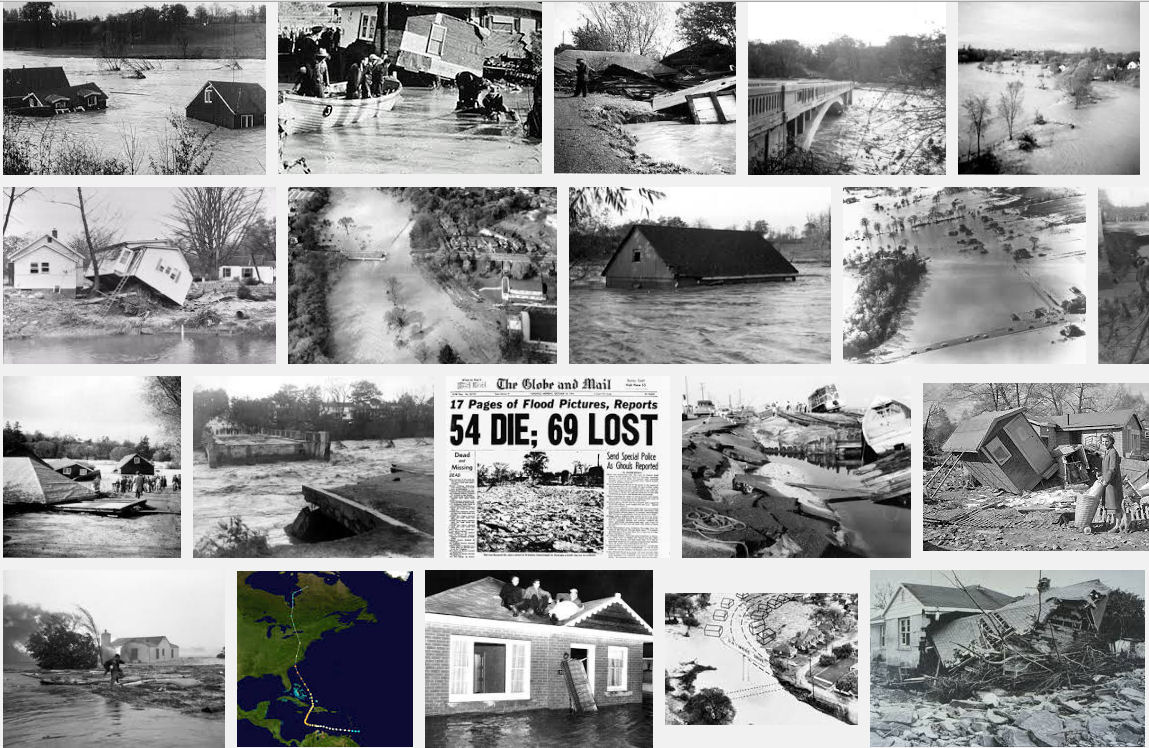

Fifty years ago on the morning of October 16, Torontonians awoke to the inconceivable: their city ravaged by a hurricane. Hazel had left 81 people dead, thousands homeless, and a city in shock.

After three days of rain, many went to bed on the night of Oct. 15, 1954 convinced they were in for another safe but soggy night. Hurricane Hazel had wreaked havoc in the Caribbean and Carolina, but here in Toronto, where hurricanes were nothing to fear, Hazel was already old news. Misled by this cozy belief, which was supported by low-key weather reports, most expected Hazel to lose punch around the Allegheny Mountains before turning eastward.

They we were wrong. Worse, they were unprepared.

Hazel pushed past New York and crossed Lake Ontario. As it reached the north shore it collided with strong cold front, saturating an unsuspecting Toronto. With awesome force, the hurricane’s 72-mile-per-hour gusts and billions of gallons of rain turned full rivers into raging torrents that washed out bridges, undercut asphalt, tossed large vehicles, submerged buildings, and killed with mind-boggling swiftness. It changed our landscape, and inflicted $25 million in damage.

“Trees and hydro lines were down,” recalls Toronto author Anne Dublin, who grew up on Manning Avenue and wrote about the hurricane in Written in the Wind, her novel for young adolescents. “There were strong winds and rain. All over the place [were] branches, lawn furniture, garbage cans…. We were all terrified. Toronto had never been subjected to this kind of weather before. We were shocked and surprised. The weather reports had been mild. No one was prepared.”

Local architect Paul Martel, chair of the Annex Residents Association’s parks and trees committee, also remembers that night.

“I was alive in 1954, a high school student, and have vivid memories of Hazel in the city I lived in, with flooded streets, mud and debris everywhere, and torrential endless rains driven by gale force winds,” he says. “It was both awesome and terrifying.”

For all Hazel’s fury, however, flooding and devastation in the Annex was not nearly as bad as it was along the watersheds of the Humber, Don and Rouge rivers, where people lived on exposed floodplains.

“As far as I recall the local damage was not as great as in the flood plains and watercourses outside the downtown,” says Martel, “Open watercourses need some interceptory vegetation, plants and trees, on their banks to mitigate and temper the volume of water in extreme conditions such as a violent storm and rainfall.”

Marty Wiener of Wiener’s Home Hardware was born just after Hazel.

“Everything in the basement was on pallets after that,” he recalls of his family’s Wilson Avenue and Bathurst Street home. “I can remember a four-foot-high water mark in the basement.” There was, however, no lasting damage to the Bloor Street store his great-grandfather opened in 1924, even though the Annex sits on three old waterways (Garrison, Taddle, and Castle Frank creeks) that used to flow aboveground, down to Lake Ontario.

The city buried and converted the creeks years ago, and Martel says it’s interesting to speculate what would have happened had they remained aboveground.

“Perhaps if we had the open Taddle Creek and Castle Frank Creek and Garrison Creek watercourses flowing in their natural state, the urban development patterns and city planning grids would have been quite different from the as-built solutions,” says the architect; “then we would have had the water from Hazel’s deluge really flowing down those creeks.”

One lasting impact of the storm was the 1957 unification of four existing conservation authorities that formed the Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, now the Toronto and Region Conservation.

Motivated by core principles of public safety, education, and action, the conservation authority studied flood control, purchased floodplains, cultivated our vast parklands, and shared their knowledge with policymakers and the public to help prevent floods in the future.

(Gleaner News, Toronto)