Naturalist’s legacy is close-knit community

A history of life in the valley

By Tom G. Kernaghan

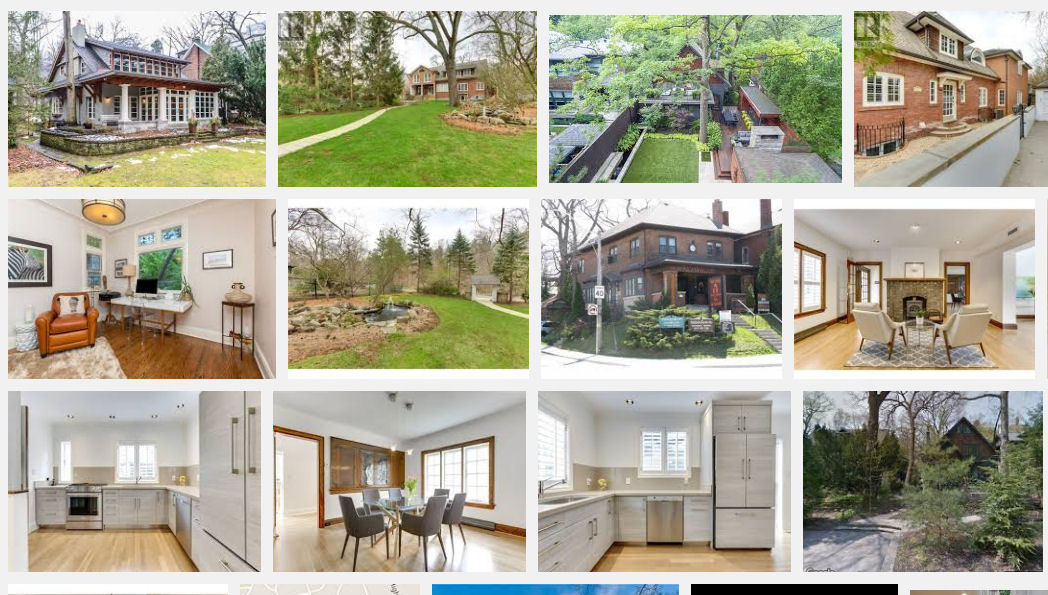

One of the city’s most unique streets lies hidden in a valley in northeast Swansea. Sheltered by Bloor Street, Ellis Park Road, and High Park, Wendigo Way for generations has been treasured for its dramatic topography, deep seclusion, and enchanting sylvan beauty.

The neighbourhood was established shortly before the First World War, when naturalist J.A. Harvey split the land into five lots and sold them to owners who then built their own houses. Located just outside the city boundary, the enclave became even more obscure behind the massive Bloor Street landfill project that connected High Park to Swansea between 1914 and 1916.

Called the valley by locals, Wendigo Way has attracted many prominent figures. Harvey himself was elected Swansea’s first reeve (head of town council) in 1926. Jim J. Addy, Village of Swansea lawyer and deputy reeve (1928 – 29), was an early resident, and William James Stewart, Toronto mayor (1931 – 34) during the Christie Pits Riot of 1933, had a cottage on the street.

For the people of the valley, however, some of the best neighbours were, and are, the trees.

“The park was our back yard,” says Chris Kurata, a lawyer and writer who grew up on Wendigo Way and in Swansea during the late 1950s and 1960s. “We had no fear. “

Kurata’s grandfather, Takatsuna Kurata, bought land on the street in 1911 after coming to Canada from the United States and Japan. An entomologist and nature lover, he became a game warden of High Park. He also worked closely with Sir Byron Edmund Walker, one of the ROM’s founders, and was friends with many influential figures, including Dr. Benjamin Apfelberg, Chief of Forensic Psychiatry at Bellevue in New York— all of whom visited Wendigo Way and High Park.

“It’s an overwhelming gift, from the standpoint of a naturalist,” says Kurata. “Its beauty is beyond comprehension.”

He recalls foxes, and children running barefoot, swimming, fishing, boating, and playing in the forest. People even had what might be called spiritual relationships with particular trees.

But the trees served many practical purposes as well. The valley, though marshy on the park side, is sandy on the Swansea side. Kurata’s grandfather used interlocking logs to secure the foundation of his house, the design of which he based on Queen Anne’s summer cottage. And many of the street’s initial homeowners used local oak for banisters, flooring, and other finishing touches.

“It was a great way to grow up,” says Kurata, whose father, Lucien, a judge, became the village’s last reeve, in 1964. “I’ve always been in touch with it,” he says, though his family left Swansea in 1968.

In the years since, newcomers have arrived, and stayed. To this day, the turnover rate in the community remains remarkably low.

“We had never seen anything remotely like this,” recalls resident Dawn Napier, who moved to Wendigo Way with her husband in 1983. “And we looked all over the city.”

Like others, she quickly became part of High Park’s untamed northwest region. She recalls neighbourhood children going there to play games like hide and seek.

“We all have a sense of stewardship toward the park,” says Napier. “And the wetlands of this area are designated as an ANSI—an Area of Natural and Scientific Interest. It’s like its own little world.”

She adds that the residents, who are quite diverse, also share close ties.

“It’s easy to get to know people,” says David McAlpine, who came to Wendigo Way from Australia in 1973. He and his wife “stumbled on it” and were immediately attracted to it. “We’ve become quite friendly with people here. There’s a good sense of community.”

“We drove through and liked it,” recalls 90-year-old Wolfgang “Wolf” Schmidt, who arrived in 1957 with his wife and is now the oldest person in the community. “People not only knew each other,” says Schmidt, “they were friends.”

Since the beginning, Wendigo Way has staved off significant change and maintained its unique charm and diverse character, even after Swansea was amalgamated into Toronto in 1967.

“It was sweetly insular,” reflects Kurata. “We were blessedly unaware.”

(Gleaner News, Toronto)